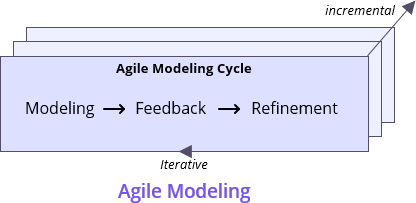

Embracing an iterative and incremental process –

Risk-driven and focuses on attacking significant project risks early

Agile Modeling (AM), as defined by Scott Ambler, adapts modeling practices to thrive in iterative, incremental, and highly adaptive environments like Scrum, Kanban, or other Agile frameworks. Rather than producing comprehensive upfront designs, Agile Modeling treats modeling as a lightweight, just-in-time activity that supports delivery while aggressively addressing the highest project risks first.

The process is fundamentally iterative (repeat cycles of modeling → feedback → refinement) and incremental (building understanding and artifacts in small, valuable pieces). It is explicitly risk-driven: teams prioritize modeling efforts that help identify, mitigate, or eliminate the most significant uncertainties and threats early—often in “Sprint 0” (Inception), during initial envisioning, or through ongoing model storming sessions.

This risk-focused approach aligns perfectly with Agile’s emphasis on delivering working software frequently while embracing change. By attacking big risks early, teams reduce the likelihood of late surprises, wasted effort, and costly pivots.

Below are the core principles of Agile Modeling (drawn from Ambler’s foundational work), with many practical, real-world examples showing how they manifest in projects, especially when combined with UML and tools like Visual Paradigm.

- Model With a Purpose Every model or diagram must serve a clear, specific goal—never model “just because” or for completeness. Ask: “What question does this answer? Who needs it? For how long?”

- Practical examples:

- In a fintech startup building a loan approval app, the team only models the credit scoring workflow (activity + sequence diagrams) because the biggest risk is regulatory compliance on decision logic. They skip detailed UI wireframes until user testing feedback demands it.

- During a retail POS system upgrade, the team creates a quick deployment diagram solely to evaluate cloud vs. on-prem hosting costs and latency risks—no extraneous class diagrams until needed.

- A healthcare team models only the patient consent flow (use case + state machine) early to de-risk HIPAA violations, ignoring non-critical admin reports.

- Maximize Stakeholder ROI Invest modeling effort only where it delivers the highest value to stakeholders (time, money, quality, risk reduction). Focus on artifacts that reduce uncertainty or enable better decisions. Practical examples:

- An e-commerce team spends half a day on a high-level component diagram to convince stakeholders that microservices will handle Black Friday scale—securing budget approval and avoiding a monolithic rewrite later.

- In a SaaS CRM project, modeling key integration points (sequence diagrams for API calls) early prevents a vendor lock-in surprise that could have delayed launch by quarters.

- A logistics company models warehouse-robot routing risks (activity diagram with swimlanes) to justify investing in simulation software, saving millions in inefficient deployments.

- Travel Light (and related: Incremental Change) Keep models minimal—create only what’s needed now, evolve incrementally, and discard when obsolete. Avoid “traveling heavy” with over-maintained documentation.

- Practical examples:

- A mobile game team sketches temporary sequence diagrams on a digital whiteboard during sprint planning to clarify multiplayer sync logic, then deletes them once implemented—no long-term maintenance burden.

- In an IoT smart-home platform, the team incrementally refines a composite structure diagram for device communication only as new hardware is added, never freezing an “as-is” version.

- During bug-fix sprints, developers model storm a small communication diagram for a failing payment retry loop—fix implemented, diagram archived or deleted.

- Assume Simplicity Start with the simplest explanation/design that could possibly work; complexity is added only when proven necessary.

- Practical examples:

- A task management app team assumes a simple pub/sub notification model instead of complex event sourcing—proven sufficient after load testing, avoiding unnecessary Kafka infrastructure.

- In a telemedicine platform, the simplest class diagram for Appointment (no inheritance hierarchies) suffices until multi-specialty scheduling complexity emerges.

- An edtech team models user progress tracking with basic state machine instead of full gamification ontology—simplicity wins until analytics show need for badges/levels.

- Embrace Change Models are living artifacts—expect and welcome evolution as understanding grows or requirements shift.

- Practical examples:

- A delivery app team starts with a basic use case diagram for “Schedule Delivery”; after user feedback, they extend it with conditional paths (rain delay, tip options) without guilt over “changing the model.”

- During migration to serverless, a team iteratively updates deployment diagrams as AWS services are swapped—no resistance to overwriting previous versions.

- In a banking KYC process, regulatory changes force extension of activity diagrams mid-sprint—team treats it as normal progress, not failure.

- Rapid Feedback Share models early and often with stakeholders, users, and team members to validate quickly and adjust.

- Practical examples:

- In daily stand-ups, a dev team projects a freshly sketched sequence diagram of auth token refresh—immediate feedback catches a missing edge case before coding.

- During sprint review, stakeholders review a timing diagram for real-time bidding in an ad-tech platform—spot latency risks and pivot design within the sprint.

- A non-technical product owner walks through a use case flow-of-events document—catches business rule misunderstanding early, saving rework.

- Working Software Is Your Primary Goal (and Quality Work) Modeling exists to support building working, high-quality software—not as an end in itself. Strive for “good enough” models that enable quality code.

- Practical examples:

- A team generates code stubs from class diagrams in Visual Paradigm, then refines via TDD—model supports working software, doesn’t delay it.

- In a legacy modernization, reverse-engineered class diagrams guide refactoring only enough to make tests pass—focus remains on delivering functional increments.

- During CI/CD pipeline setup, a simple package diagram organizes model elements for automated validation—ensures quality without slowing delivery.

- Multiple Models No single diagram tells the whole story—use the right view (structural, behavioral, etc.) for the current risk or question.

- Practical examples:

- To de-risk concurrency in a chat app: sequence diagram for message ordering + state machine for connection lifecycle + activity diagram for offline handling.

- In an autonomous vehicle subsystem: composite structure for sensor integration + timing diagram for real-time constraints + deployment for edge vs. cloud compute.

- A supply chain dashboard uses package diagram for organization, class for domain, and interaction overview to tie reporting flows together.

By following these principles, Agile Modeling becomes a powerful enabler for risk-driven development: teams front-load modeling on the riskiest areas (architecture, key integrations, critical workflows), iterate rapidly, stay lightweight, and keep the focus on delivering value incrementally. This prepares you perfectly for the use-case-driven requirements we’ll explore in Module 2, where models directly attack functional and stakeholder risks early in the lifecycle.